We’ve heralded the 1911 Vauxhall Prince Henry as one of the most influential cars of the 20th century, being perhaps the first proper production sports car. But what was the inspiration behind it? And who was Prince Henry?

His name was actually Heinrich, and he was Prince of Prussia (the dominant state within the German Empire), brother to Kaiser Wilhelm, grandson to Queen Victoria. A very keen motorist, for four summers he arranged the Prinz-Heinrich-Fahrt, translating as ‘tour’ but more like a road rally and reliability trial. And it was in an effort to win his trophy that the hot Vauxhall was created.

The first tour of 1908 ran from Berlin to Stettin (now Szczecin) on the Baltic coast, west to Hamburg, down to Trier on the Luxembourg border and finally east to Frankfurt – a total of some 1370 miles. Special prizes would be given for speed, reliability, hillclimbing and more.

The regulations were designed to ensure proper touring cars, not racing specials: minimum kerb weight 860kg, four or six cylinders with piston area and bore limits, two independent brakes, reverse gear, front and rear lights, horn, number plates. This attracted 129 entries from various marques, some of them still familiar today, most entirely forgotten.

Enjoy full access to the complete Autocar archive at the magazineshop.com

The formula didn’t work as intended. Many cars had special bodywork and were driven not by ‘gentlemen’ but by racers – including Dorothy Levitt in the sole British car, a Napier, and the overall winner, Benz factory man Fritz Erle -“to the dissatisfaction and disgust of legitimate competitors”, reported Autocar. We also regretted that the results of each stage hadn’t been announced to the amassed public.

Unsurprisingly, Prince Heinrich changed his regulations for 1909, handicapping factory drivers and defining body and cabin shapes. He also made the route far more adventurous: from Berlin to Breslau (now Wroclaw in southern Poland), south over the Tatra mountains to Budapest, west to Vienna and back over the Salzburg Alps to Munich. This time the winner was Opel co-owner Wilhelm Opel, followed by Count Kolowrat for Bohemian firm Laurin & Klement (now Skoda).

In 1910, we were disappointed to report that again “the majority were of the torpedo body type, the radiators being brought to a sharp point and all care being taken to do away with every inch that might act as a resistance to the wind. The Benz cars, with their wheels entirely encased in tin, resemble nothing so much as huge slippers.” The route went south-west from Berlin to Kassel, down to Nuremberg, through the Black Forest to Metz (now in France) and back east to Homburg (near Frankfurt).

Some unpleasantness befell the tourists this time: one car was immolated by a spectator’s discarded match while refuelling, another hit a tree, killing its driver, and all were drenched by thunderstorms. The winner was Ferdinand Porsche in an Austro-Daimler of his own design – which was promptly added to the Austrian manufacturer’s range, with its “remarkably interesting” engine.

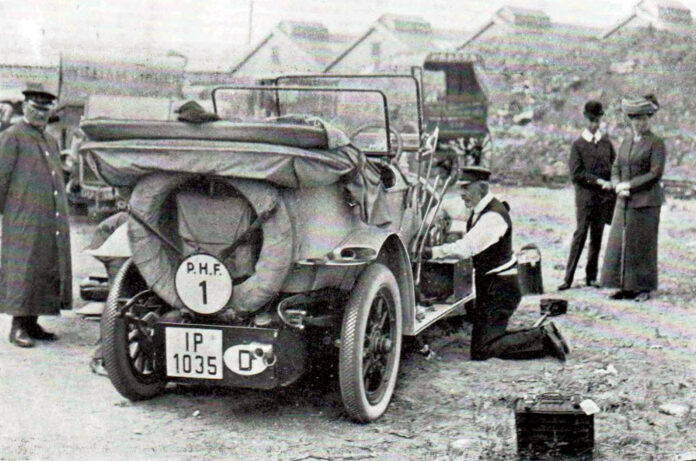

Vauxhall likewise began selling its specially bodied 20hp tourer, which had done well in terms of both reliability and speed. Chief engineer Percy Kidner told Autocar: “The Germans’ interpretation of the rules was refined to a degree. His Royal Highness was much disappointed that his rules had not produced the bodies he wished.

“The drivers were all good sportsmen and behaved to us all in a very sportsmanlike manner.

“The roads in Prussia are so bad that our Irish highways are billiard tables by comparison, and I was filled with admiration at the way the Continental cars stood the fearful bucketing they underwent in being driven at some 30mph over them.”

Earlier that year, while visiting Britain, Prince Heinrich had agreed with King Edward to plot his 1911 route across the Channel. It went from Homburg up to Bremerhaven, via steamer to Southampton, up to Edinburgh and back to the coast.

Speed trials were removed after the previous year’s crash and entrants grouped into two national teams. We had much praise for the event, admiring equally the German and British cars and drivers, and noted hopefully: “Ignorance is the great cause of racial jealousy. It may come about that rival nations by knowing each other better can keep their rivalry to certain forms which will not kill friendship.”