Highlights

- Potential 25% tariff on all goods from Canada, Mexico into the

US - Virtually all automakers and suppliers would be impacted

- Potential for spring 2025 implementation

Introduction

US President Donald Trump is assessing a 25% tariff on all goods

from Canada and Mexico. While this would impact all industries,

S&P Global Mobility looks at the specific impact of Trump's

automotive tariffs on vehicle assembly.

President Trump has said the tariff could be applied as soon as

Feb 1, 2025. At time of writing, the latest intelligence suggests a

more measured approach may still win out, though tariffs could be

applied by spring 2025.

Regardless of timing, these blanket tariffs would have a massive

impact on the auto industry. It is also likely that Canada and

Mexico will reciprocate through an equal or 'representative'

tariff. Though there is no indication of what that retaliation

might look like at this time, we could see another degree of

complexity if these countries imposed their own tariffs on

automotive components imported from the US and used in Canadian or

Mexican assembly.

From a trade perspective, the move is likely to bring early

changes to the USMCA trade agreement – and make those changes more

favorable to the US. The USMCA trade agreement is due for review in

July 2026.

There are approximately 5.3m light vehicles built in Canada and

Mexico, with about 70% of these destined for the US. Further, many

US-built vehicles use Canadian or Mexican-sourced propulsion

systems and component sets; those components would see a tariff as

well, increasing costs for vehicles produced in the US. Virtually

no OEM or supplier operating under the USMCA is immune.

US automotive tariffs: Current

situation

The current tariff-free structure stems from successive trade

agreements starting in 1965 with Canada and including Mexico in

1994 with NAFTA, which evolved into USMCA in 2020. Free trade has

created a streamlined production ecosystem among the three

partners. Customers and the industry benefit from zero tariffs if

specific North American value-add criteria are met. For decades, a

largely stable environment has enabled a trading ecosystem to

evolve.

In 2024, the US imported some 3.6m light vehicles from Canada

and Mexico, representing 22% of all vehicles sold in the US. Mexico

is currently the largest source of US light-vehicle imports,

passing Japan, South Korea and all of Europe.

Vehicle production in Mexico and Canada has been a significant

part of sourcing strategies for several automakers for decades.

Ford and GM have been producing vehicles in Canada and Mexico for

around 100 years, Volkswagen has been producing vehicles in Mexico

since 1967 and Nissan since 1992. Toyota and Honda have also been

producing vehicles in Canada since the mid-1980s, each opening

plants in Mexico this century.

Automakers and suppliers produce components throughout the

region, with engines among the higher cost-impact items. Over the

years, production in Canada has waned while production in Mexico

has increased, though both are significant in the ecosystem.

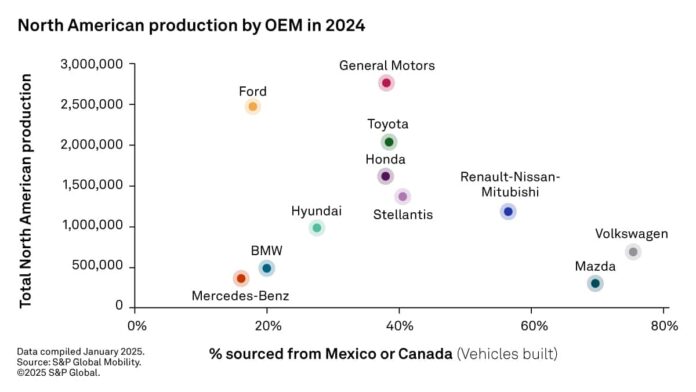

Regardless of automaker, in 2024, S&P Global Mobility estimates

that about 54% of US light-vehicle sales were produced in the US,

15% in Mexico and just under 7% from Canada.

The automakers with the longest history of vehicle production in

Mexico also see that capacity more deeply integrated. Mexico is an

attractive sourcing option for Detroit-based OEMs, as well as for

Volkswagen. In 2024, about 23% of Stellantis sales were sourced

from Mexico, while GM sourced 22% and Ford just under 15%.

Beyond the D3, Nissan sources about 27% of its US sales from

Mexico, Honda nearly 13%, and Toyota and Hyundai at 8% each.

Volkswagen is the most exposed to tariff risk, with over 43% of its

US sales sourced from Mexico.

A 25% tariff scenario

Here we presume the US introduces a 25% tariff on Canadian and

Mexican value add, though timing is uncertain. All vehicles and

components moving from Canada or Mexico to the US would face this

tariff on value added outside the US.

Canada and Mexico are likely to implement tariffs in response.

In this scenario, tariffs apply only to the manufactured value of

the component or vehicle added outside the US, not the final

customer-facing MSRP.

A 25% duty on the average $25,000 landed cost of a vehicle from

Mexico and Canada would add $6,250. Importers are likely to pass

most, if not all, of this increase to consumers. With average

vehicle prices near all-time highs, this additional tariff would

put further strain on affordability.

If components and parts are also subject to the 25% tariff,

vehicles produced in the US with any components sourced from Canada

or Mexico would also see costs rise by 25%. Given the free flow of

components across borders, the tariff would impact most vehicles

produced in the US as well.

Impact on automaker

production

S&P Global Mobility sees automaker exposure in three broad

levels. Vehicles produced in the US with US-sourced powertrains and

propulsion systems (among the most expensive components) will have

the least exposure, clearly.

Vehicles built in the US will have another level of exposure;

examples here include the Ford F-Series pick-ups and Mustang cars

with engines from Canada, as well as the Mazda CX-50 which sources

engines from Mexico.

Vehicles at significant exposure risk are those built in Canada

or Mexico, particularly high-volume products where automakers have

little opportunity for re-sourcing. Among the vehicles in that

category are full-size pick-up trucks from GM and Stellantis, as

well as the Toyota RAV4.

Impact on automotive

suppliers

Supplier impact can also be significant, and this will increase

vehicle prices to consumers in indirect, nontransparent ways. We

could see automakers pull back production on tariffed vehicles;

similar to the reaction to the semiconductor shortage and other

Covid-related supply chain shortages, some automakers could slow

production until sales are lost due to lack of product. Reducing

production affects supplier sales and contracts.

OEMs may serve as the main support for tariff exposure since

many smaller tier 1 and tier 2 suppliers lack the capital to cover

ongoing tariffs without help from their customers. Some suppliers

may invoke Force Majeure, refusing to supply parts if they are not

quickly compensated for tariff costs.

However, many OEM tier 1 supplier contracts likely follow

ex-works or free carrier (FCA) incoterms, where parts are delivered

to a local site and the OEM pays duties to export the supplier's

parts to the final assembly location. In that case, force majeure

would not apply and automakers would need to pay the tariff.

Consequently, the impact is more likely to affect smaller suppliers

working with Tier 1s

Summary

A tariff against Canada and Mexico could significantly disrupt

the economics of the region, even if lower than the 25% being

considered. Among the open questions will be how long the tariff

might be in play; given the justification is related to immigration

and stopping the flow of illegal drugs, what metrics will be in

place for Canada and Mexico to meet to see the tariff lifted

again?

Our assumptions remain true whether the tariff is enacted on

February 1 or later. It is also possible that the tariff is tabled

and worked into a larger renegotiation of the USMCA free trade

agreement. However, some level of tariff being deployed against

Canada and Mexico seems to inch closer toward reality.

A full-length analysis is available to

AutoInsight,

AutoIntelligence and AutoTech

Insight customers through the respective web portals